It is common to hear references of the famed Seven Hills of Rome throughout the city’s history because they are so intertwined with Rome’s foundation, the original delineation of the city limits and its consolidation of power over time. Nowadays the hills more closely resemble land ridges than proper mounts because constructions and developments over the centuries have made some of them difficult to identify.

1. The Palatine

1. The Palatine

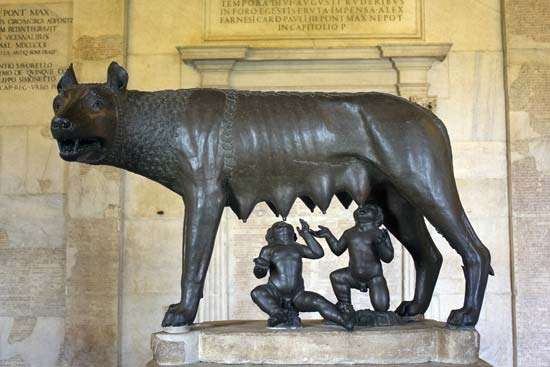

The most famous hill, Palatine Hill, is the location where the city of Rome is thought to have been founded. According to Roman mythology, Romulus and Remus were abandoned in the Tiber River and were saved thanks to a she-wolf who suckled them to life; they were then rescued and raised by a shepherd and his wife. Born natural leaders, they vied over where to establish the Roman Empire and Romulus eventually killed Remus, laying the foundation for the city on Palatine Hill. Excavations show that people have lived in the area since the 10th century BC and during the city’s Classical period, Roman emperors and elites lived upon this hill. Emperors Augustus, Tiberius and Domitian all had palaces built on Palatine Hill, most likely in an effort to appeal to historic foundations for their leadership. There are many important ruins to see including ancient imperial palaces, a hippodrome/stadium and landscaped gardens.

The bronze statue of the maternally ferocious wolf, now in the city’s Capitoline Museums, is one of the best-known works among the thousands of masterpieces in Rome. The Lupercal, the supposed cave of the she-wolf, was maintained as a shrine at least until the fall of the empire. On the same side of the Palatine, “Romulus’s House,” a timber-framed circular hut covered in clay-plastered wickerwork, also was kept in constant repair in ancient times. Modern excavations have revealed the emplacement of just such Iron Age huts from the period (8th–7th.C. BCE) given in the fable for the founding of Rome. In addition, in 2007 a vaulted sanctuary thought to be the long-lost Lupercal was discovered 16 metres below the surface of the Palatine.

The wolf traditionally has been identified as Etruscan, c. 500–480 BC, though some early 21st.C. research suggests medieval origins. The twins date from the 16th.C.

The wolf traditionally has been identified as Etruscan, c. 500–480 BC, though some early 21st.C. research suggests medieval origins. The twins date from the 16th.C.

By the 3rd.C. BCE the Palatine was a superior residential district. Rome’s first emperor, Augustus, was born there in 63 BCE and continued to live there after he became emperor. His private dwelling, built about 50 BCE and never seriously modified, still stands. It is known as the House of Livia, for his widow, and has small, graceful rooms decorated with paintings. Other private houses, now excavated and visible, were incorporated into the foundations of the spreading imperial structures, which eventually projected down into the Forum on one side and onto the Circus Maximus on the other. The emperor Tiberius built a palace to which Nero, Caligula, Trajan, Hadrian, and Septimius Severus made additions. The biggest and richest structure of all was created for Domitian (reigned 81–96 CE), whose architect achieved feats of construction engineering not seen before in Rome. Parts of the lavish structure—the richly marbled, centrally heated dining hall of which is among the chambers visible today—were occupied by popes after there were no more emperors, and then the hill was abandoned.

After some six centuries the great Roman families returned to the Palatine, planting 16th.C. pleasure gardens and pavilions over past glories. A whole set of rooms from the private wing of Domitian’s palace was preserved by incorporation into the Villa Mattei. Atop Tiberius’s palace, the Farnese family built two aviaries and a garden house and laid out one of Europe’s first botanical gardens—some parts of which have escaped archaeological excavation.

After some six centuries the great Roman families returned to the Palatine, planting 16th.C. pleasure gardens and pavilions over past glories. A whole set of rooms from the private wing of Domitian’s palace was preserved by incorporation into the Villa Mattei. Atop Tiberius’s palace, the Farnese family built two aviaries and a garden house and laid out one of Europe’s first botanical gardens—some parts of which have escaped archaeological excavation.

2. The Capitoline

2. The Capitoline

The Capitoline Hill was the fortress and asylum of Romulus’s Rome. The northern peak was the site of the Temple of Juno Moneta (the word money derives from the temple’s function as the early mint) and the citadel emplacements now occupied by the Vittoriano monument and the church of Santa Maria d’Aracoeli. The southern crest, sacred to Jupiter, became in 509 BCE the site of the Temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus, the largest temple in central Italy. The tufa platform on which it was built, now exposed behind and beneath the Palazzo dei Conservatori, measured 62 by 53 metres, probably with three rows of six columns across each facade and six columns and a pilaster on either flank. The first temple, of stuccoed volcanic stone quarried at the foot of the hill, had a timber roof faced with brightly painted terra-cottas. Three times it burned and was rebuilt, always of richer materials. The temple that Domitian built was marble with gilded roof tiles and gold-plated doors. It was filled with loot by victorious generals who came robed in purple to lay their laurel crowns before Jupiter after riding in triumph through the Forum. The antique pavings of the Clivus Capitolinus, the road leading up the hill from the Forum, survive today. In this centre of divine guidance, the Roman Senate held its first meeting every year. Centuries later, in 1341, the Italian poet Petrarch was crowned with laurel among the ruins of this capitol.

The church of Santa Maria d’Aracoeli, built before the 6th.C. and remade in its present form in the 13th.C. is lined with columns rifled from Classical buildings. It is the home of “Il Bambino,” a wooden statue (originally a 15th.C. statue; now a copy) of the Christ Child, who is called upon to save desperately ill children.

The church of Santa Maria d’Aracoeli, built before the 6th.C. and remade in its present form in the 13th.C. is lined with columns rifled from Classical buildings. It is the home of “Il Bambino,” a wooden statue (originally a 15th.C. statue; now a copy) of the Christ Child, who is called upon to save desperately ill children.

The Capitoline today, still the seat of Roman government, is little changed from the 16th.C. design conceived of by Michelangelo—one of the earliest examples of modern town planning. The resulting Piazza del Campidoglio, completed after Michelangelo’s death, is framed by three palaces: the Palazzo Senatorio, the Palazzo dei Conservatori, and the Palazzo Nuovo (opposite and identical to the older Palazzo dei Conservatori). The centrepiece of the piazza is a replica of a bronze equestrian statue of Marcus Aurelius.

The Palazzo Senatorio (“Senate Palace”) incorporates remains of the facade of the Tabularium, a state records office constructed in 78 BCE and one of the first buildings to use concrete vaulting and employ the arch with the Classical architectural orders. After a popular uprising in 1143 CE, a palace was built on the site for the revived 56-member Senate, supposedly elected by the people but by 1358 a body of one appointed by the pope; when it was rebuilt to Michelangelo’s design, it gained its present name.

The Palazzo Senatorio (“Senate Palace”) incorporates remains of the facade of the Tabularium, a state records office constructed in 78 BCE and one of the first buildings to use concrete vaulting and employ the arch with the Classical architectural orders. After a popular uprising in 1143 CE, a palace was built on the site for the revived 56-member Senate, supposedly elected by the people but by 1358 a body of one appointed by the pope; when it was rebuilt to Michelangelo’s design, it gained its present name.

The Palazzo dei Conservatori (“Palace of the Conservators”), on the south side of the square, was the initial site of a papal collection of Classical works offered back to the citizens of Rome by Sixtus IV in 1471. Following its completion in the 17th.C., the Palazzo Nuovo (“New Palace”; later also called the Palazzo del Museo Capitolino [Capitoline Palace]) housed a portion of the large collection. In 1734 it was opened to the public as a museum. Now occupying both the Palazzo Nuovo and the Palazzo dei Conservatori, as well as a later private palace (Caffarelli-Clementino), the Musei Capitolini (Capitoline Museums) contain only objects found in Rome, including the famed bronze she-wolf, the Capitoline Venus, and the Dying Gaul, as well as a host of portrait busts that can, in imagination, repeople the Forum just below.

3. The Aventine

Like the Palatine Hill, the Aventine Hill plays an important role in Rome’s founding myth. According to legend, when Romulus and Remus were vying for power, Romulus chose to set up his empire on the Palatine Hill while Remus opted for the Aventine Hill. Romulus ended up killing Remus but the Aventine Hill continued to be a desirable location for powerful rulers and orders through the centuries because of its strategic and easily fortifiable position overlooking the Tiber River. Today it is known for being an affluent residential area.

Though considerably built over with modern houses and traveled by modern bus lines, the Aventine still bespeaks a Rome of the past, if not the Classical past. The repeated fires that swept the city destroyed all the buildings of the era of the republic, and the Temple of Diana remains only as a street name. Under the 4th.C. church of Santa Prisca is one of the best-preserved Mithraic basilicas in the city. The basilica of Santa Sabina, little altered since the 5th century, is lined with 24 magnificent matching Corinthian columns rescued out of Christian charity from an abandoned pagan temple or palace. The Parco Savello, a small public park, was the walled area of the Savello family fortress, one of 12 that ringed the city in medieval times.

Though considerably built over with modern houses and traveled by modern bus lines, the Aventine still bespeaks a Rome of the past, if not the Classical past. The repeated fires that swept the city destroyed all the buildings of the era of the republic, and the Temple of Diana remains only as a street name. Under the 4th.C. church of Santa Prisca is one of the best-preserved Mithraic basilicas in the city. The basilica of Santa Sabina, little altered since the 5th century, is lined with 24 magnificent matching Corinthian columns rescued out of Christian charity from an abandoned pagan temple or palace. The Parco Savello, a small public park, was the walled area of the Savello family fortress, one of 12 that ringed the city in medieval times.

A romantic gem is the Piazza dei Cavalieri di Malta (“Knights of Malta Square”), designed in the late 1700s by Giambattista Piranesi, an engraver with the heart of a poet and the eye of an engineer. To the right of this obelisked and trophied square, set about with cypresses, is the residence of the grand master of the Knights of Malta (Hospitallers). The order’s headquarters were moved permanently to Rome in 1834.

4. The Caelian

Located close behind the Colosseum, the Caelian Hill was the residential district of Rome’s wealthy families during the Republic era. There are many notable churches in the area, including the three-tiered Basilica di San Clemente, the round Santo Stefano Rotondo (460–483) which may have been modeled on the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem, and the perched Basilica dei Santi Quattro Coronati, the only fortified abbey left in Rome, today sheltering nuns. The ancient Roman road Clivus Scauri is visible, highlighted with arches that likely functioned as aqueducts that carried water into the city. The Villa Celimontana public gardens are also some of the loveliest in the city.

Located close behind the Colosseum, the Caelian Hill was the residential district of Rome’s wealthy families during the Republic era. There are many notable churches in the area, including the three-tiered Basilica di San Clemente, the round Santo Stefano Rotondo (460–483) which may have been modeled on the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem, and the perched Basilica dei Santi Quattro Coronati, the only fortified abbey left in Rome, today sheltering nuns. The ancient Roman road Clivus Scauri is visible, highlighted with arches that likely functioned as aqueducts that carried water into the city. The Villa Celimontana public gardens are also some of the loveliest in the city.

The basilica of Santi Giovanni e Paolo, from the 5th.C., stands in a piazza that has few buildings later than the Middle Ages. Alongside the church are the remains of the platform of the Temple of Claudius, dismantled partly by Nero, completely by Vespasian. The round church of San Stefano Rotondo

The Hospital of St. John was founded in the Middle Ages as a dependence of the church of San Giovanni in Laterano (St. John Lateran), just off the hill, and maintains its Romanesque gateway. The Hospital of St. Thomas, established at the same period, has disappeared save for its mosaic gateway, signed by Cosmate, of the Cosmati school of carvers and decorators, and by his father, Jacobus. Nearby stands the Arch of Dolabella (10 CE), and not far away are the ruins of Nero’s extension of the Claudian aqueduct. Also on the hill is the extensive Military Hospital of Celio.

The Baths of CaracallaThe ruins of the Baths of Caracalla (c. 206–216), the public baths of the emperor Caracalla, are found on the river flats behind the Caelian Hill. Among the towering remains set in a large park, the caldarium (steam room) is now used for summer opera performances. Much of the famed Farnese family collection of marbles was stripped from these baths.

The Baths of CaracallaThe ruins of the Baths of Caracalla (c. 206–216), the public baths of the emperor Caracalla, are found on the river flats behind the Caelian Hill. Among the towering remains set in a large park, the caldarium (steam room) is now used for summer opera performances. Much of the famed Farnese family collection of marbles was stripped from these baths.

5. The Esquiline

Historically, the Esquiline Hill was famous for being the location of Emperor Nero’s Domus Aurea, "Golden House", the grandest villa built in Roman civilization which spanned to the Palatine Hill and the Caelian Hill. Excavations are currently taking place but visitors are able to admire its elaborate stucco ceilings, frescoes and incredibly ample dimensions on weekend visits of the worksite. Today the Esquiline Hill is topped with the beautiful Santa Maria Maggiore, one of the four papal basilicas of Rome and the largest church dedicated to the Virgin Mary in Rome.

After the fire of 64 CE had destroyed so much of the city, Nero undertook to rebuild more than 200 acres (81 hectares) of it as a palace for himself: seawater and sulfur water were piped into its baths; flowers were sprinkled down through its fretted ivory ceilings; and the facade was covered in gold, from which the name Domus Aurea derived. The expropriation so enraged the citizens that his successors hastened to efface all trace of Nero’s incredible palace: the ornamental artificial lake was drained, and on its bed the Colosseum was erected for free entertainment; Trajan built magnificent baths—also with free admission—atop the domestic wing of the Golden House; and Domitian converted the portico on the edge of the Forum into Rome’s smartest shopping street. The obliterators were aided by the fire of 104 CE. Less than 70 years after the Golden House had been started, nothing was left of it but a huge gilded statue of Nero, later destroyed by one of the early popes. The removal of the Golden House was so complete that later Romans could not remember where it had stood. When the domestic wing of the palace was discovered under the remains of Trajan’s Baths in the 15th.C., the rooms painted in the Pompeiian style were thought at first to be decorated grottoes. Some years later, when the painter Raphael and his friends were let down on ropes to look, the style they imitated in decorating the Vatican loggias was called grotesque.

Trajan’s Baths served as models for the Baths of Caracalla and Diocletian, which in turn served as a pattern for the basilica built by Maxentius. The bath building that housed the hot, warm, cold, and exercise rooms and the swimming pool was a huge rectangular concrete structure lined with marble. It was surrounded by a garden enclosed in an outer rectangle of libraries, lecture halls, art galleries, and other facilities of a big community centre.

Located between the Esquiline and the Palatine, the Basilica of Maxentius (also named after Constantine I, who completed it after dispatching Maxentius) was started about 311. This massive hall of justice and commerce was covered by three groin vaults with three deeply coffered tunnel-vaulted bays on either side. It was probably ruined by the earthquake of 847 and was also mined for its materials. One of the great Corinthian columns stands obelisk-like before the Santa Maria Maggiore church on the Esquiline. The head of a colossal statue of Constantine that once stood in the basilica now reposes in the courtyard of the Palazzo dei Conservatori.

6. Quirinal

Like much of the Esquiline, the adjacent Viminal and Quirinal hills lie in the heart of modern Rome. The highest of the Seven Hills, Quirinal Hill is the seat of the President of the Italian Republic who lives within the Palazzo del Quirinale. It is one of the largest palaces in the world and was originally a residence of the Pope: indeed, it has housed many important figures over the centuries, including 30 Popes, four Kings of Italy and 12 presidents of the Italian Republic. In the vicinity are many important baroque monuments and churches, including Sant’Andrea al Quirinale designed by Bernini, San Carlo alle Quattro Fontane designed by Borromini and the Quattro Fontane, a junction of fountains depicting river gods.

Like much of the Esquiline, the adjacent Viminal and Quirinal hills lie in the heart of modern Rome. The highest of the Seven Hills, Quirinal Hill is the seat of the President of the Italian Republic who lives within the Palazzo del Quirinale. It is one of the largest palaces in the world and was originally a residence of the Pope: indeed, it has housed many important figures over the centuries, including 30 Popes, four Kings of Italy and 12 presidents of the Italian Republic. In the vicinity are many important baroque monuments and churches, including Sant’Andrea al Quirinale designed by Bernini, San Carlo alle Quattro Fontane designed by Borromini and the Quattro Fontane, a junction of fountains depicting river gods.

Heavily built upon and burdened with traffic, the Quirinal seems almost flattened under the Ministry of the Interior. The ancient Baths of Diocletian (c. 298–306) are northeast of the Viminal. Some idea of their size (130,000 square yards [110,000 square metres] for the main bath block) can be gained from the fact that the church of San Bernardo was built into one of the chambers some 500 feet (150 metres) west of the central hall of the frigidarium (cold room), into which Michelangelo built the cloister church of Santa Maria degli Angeli in 1561. A portion of the Museo Nazionale Romano (National Museum of Rome) is housed in the baths complex. This matchless collection of antiquities includes wall paintings from villas, mosaics, sarcophagi, and sculptures.

The Quirinal, pierced by a modern traffic tunnel, has been a distinguished address since Pomponius Atticus, recipient of the statesman Cicero’s letters, was a resident in the 1st.C. BCE. Starting with the Crescentii, who planted the family fortress there in the Middle Ages, powerful Roman families built their homes in this location. The Palazzo Colonna, at the foot of the hill near the Via del Corso, is an art gallery open to the public; its gardens, climbing the slope to the Piazza Quirinale, contain remnants of Caracalla’s Temple of Serapis. The piazza has been graced since antiquity with two large statues of men with rearing horses, The Horse Tamers, or Castor and Pollux. Closed on three sides by palaces, the piazza opens on the fourth to a splendid view over the Tiber.

The Palazzo del Quirinale (Quirinal Palace), built by Pope Gregory XIII in 1574 as a summer palace away from the heat and malaria of the Vatican, was enlarged and embellished over the next 200 years by a succession of noted architects. The palace, with many extensions and wings, is huge, and its garden is five times as big as the building. From 1550 to 1870, the Quirinal rather than the Vatican was the official papal residence. In 1870 it became the royal palace of the new Kingdom of Italy and in 1948 the presidential palace. Both monarchs and presidents, however, have preferred to inhabit the homier palazzetto (“little palace”) at the far end.

The Palazzo del Quirinale (Quirinal Palace), built by Pope Gregory XIII in 1574 as a summer palace away from the heat and malaria of the Vatican, was enlarged and embellished over the next 200 years by a succession of noted architects. The palace, with many extensions and wings, is huge, and its garden is five times as big as the building. From 1550 to 1870, the Quirinal rather than the Vatican was the official papal residence. In 1870 it became the royal palace of the new Kingdom of Italy and in 1948 the presidential palace. Both monarchs and presidents, however, have preferred to inhabit the homier palazzetto (“little palace”) at the far end.

The handsome buildings opposite are the stables (1730–40), built on the site of the Crescentii 10th.C. stronghold. This zone is now used as a site for major art exhibitions. The Palazzo della Consulta (1734), erected for part of the papal administration, became the home of the Italian Constitutional Court in the 1950s. The Palazzo Pallavicini-Rospigliosi, built by a cardinal of the Borghese family in 1603, is still a private house.

The Palazzo Barberini farther up the Quirinal, constructed during 1629–33 on the site of the old Palazzo Sforza, was occupied by the Barberini family until 1949. Part of the collection of the Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Antica (National Gallery of Ancient Art) is housed here, the rest across the river in the Palazzo Corsini in the Trastevere rione (district). The pictures, most of them works by celebrated masters, were contributed by distinguished families, including the Barberini. Architecturally, the Palazzo Barberini is important because it marks a departure from the heavy-set four-square town houses of the early and High Renaissance. In the Rome region, only country villas had been built on so open a plan, with two wings coming forward from an open, arcaded facade. Further, it pioneered the Baroque style in domestic architecture.

Carlo Maderno, who put the facade on St. Peter’s Basilica, made the plans for the Palazzo Barberini, which were carried out after his death by Gian Lorenzo Bernini, assisted by Francesco Borromini. Each of these two rivals has a church just around the corner. After 20 years of apprenticeship, Borromini was given his first chance to do his own building. It was a church at an impossibly tiny site at the crossroads of Quattro Fontane (“Four Fountains,” one of which is built into a niche in the church wall), but his creation, San Carlo alle Quattro Fontane, was a triumph. To his revolutionary solutions for site problems, for which he employed a brilliant variation on the oval, Borromini added a facade in 1667, the year he died, which responded to the waves of motion generated by the spatially complex interior. His work created a sensation, and his ideas were seized upon by Baroque artists, especially from other countries. Bernini’s Sant’Andrea al Quirinale is also small, but it took 12 years to build (1658–70), late in his career. An oval building with the naves sculpted into the outer wall, it enlarges on concepts advanced by Michelangelo. Bernini’s use of coloured marbles and shrewd lighting effects gives the small structure extra dimension. Nearby is the Teatro dell’Opera (Opera House), built in 1880 by Achille Sfondrini. It was acquired by the state in 1926 and is Rome’s most important lyric theatre.

Carlo Maderno, who put the facade on St. Peter’s Basilica, made the plans for the Palazzo Barberini, which were carried out after his death by Gian Lorenzo Bernini, assisted by Francesco Borromini. Each of these two rivals has a church just around the corner. After 20 years of apprenticeship, Borromini was given his first chance to do his own building. It was a church at an impossibly tiny site at the crossroads of Quattro Fontane (“Four Fountains,” one of which is built into a niche in the church wall), but his creation, San Carlo alle Quattro Fontane, was a triumph. To his revolutionary solutions for site problems, for which he employed a brilliant variation on the oval, Borromini added a facade in 1667, the year he died, which responded to the waves of motion generated by the spatially complex interior. His work created a sensation, and his ideas were seized upon by Baroque artists, especially from other countries. Bernini’s Sant’Andrea al Quirinale is also small, but it took 12 years to build (1658–70), late in his career. An oval building with the naves sculpted into the outer wall, it enlarges on concepts advanced by Michelangelo. Bernini’s use of coloured marbles and shrewd lighting effects gives the small structure extra dimension. Nearby is the Teatro dell’Opera (Opera House), built in 1880 by Achille Sfondrini. It was acquired by the state in 1926 and is Rome’s most important lyric theatre.

7. Viminal

Sandwiched in between the Esquiline and Quirinal Hills, the Viminal Hill is the smallest of the Great Hills of Rome. It is notable for being the location of Rome’s Termini Train Station, the Teatro dell’Opera and houses two of four National Museums of Rome: Palazzo Massimo, with beautiful frescoes from the House of Livia and the bronze statue of the Boxer at Rest, and the ruins of the Baths of Diocletian which were originally the largest baths in ancient Rome.

Sandwiched in between the Esquiline and Quirinal Hills, the Viminal Hill is the smallest of the Great Hills of Rome. It is notable for being the location of Rome’s Termini Train Station, the Teatro dell’Opera and houses two of four National Museums of Rome: Palazzo Massimo, with beautiful frescoes from the House of Livia and the bronze statue of the Boxer at Rest, and the ruins of the Baths of Diocletian which were originally the largest baths in ancient Rome.

2 other hills

Behind the Piazza del Popolo is the Pincio (Pincian Hill). During the Roman Empire the Pincio was covered with villas and gardens, but it was made into a public park only in the 19th.C.. Toward sunset many Romans arrive to stroll along the Pincio promenade.

On the hill is the Villa Borghese, which the Italian government purchased, along with its contents and grounds, at the turn of the 20th.C.. The grounds are now an extensive park containing numerous museums, academies, monuments, natural features, and other attractions. In the villa itself, the Galleria Borghese’s collection features several Caravaggios, Titian’s Sacred and Profane Love, and Antonio Canova’s Neoclassical nude statue of Pauline Bonaparte, for a time a Borghese princess, as Venus Victrix.

The 1544 Villa Medici was bought by Napoleon in 1801 to house the Accademia di Francia (French Academy), which is still in occupation. This academy, founded in 1666, is the oldest of many national academies established from the 17th.C. to the 19th.C. to give architects, artists, writers, and musicians the opportunity to study the vast textbook that is the city itself and to use its museums and libraries.

The 1544 Villa Medici was bought by Napoleon in 1801 to house the Accademia di Francia (French Academy), which is still in occupation. This academy, founded in 1666, is the oldest of many national academies established from the 17th.C. to the 19th.C. to give architects, artists, writers, and musicians the opportunity to study the vast textbook that is the city itself and to use its museums and libraries.

The Villa Giulia was a typical mid-16th-century Roman suburban villa, conceived not as a dwelling but as a place for repose and entertainment during the afternoon and early evening. It houses the Museo Nazionale di Villa Giulia (Villa Giulia National Museum), which has a collection of Etruscan art and artifacts of singular beauty and historical value.

Other attractions of the Borghese grounds include the Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna (National Gallery of Modern Art), founded in 1883, with an important collection of 19th.C. and 20th.C. Italian art, and the Bioparco–Giardino Zoologico (Biopark–Zoological Garden), established in 1911.

Across the river, behind the river plain of Trastevere, is the Gianicolo (Janiculum Hill). The Janiculum crest was made into a park in 1870 to honour Giuseppe Garibaldi for his heroic but unsuccessful defense of the short-lived Roman Republic of 1849.